Optimal Party Theory, Part 1 of 4

A painful truth that I have realized after many years of attending, organizing, and (quietly) criticizing parties: most parties are not great.

This comes down, basically, to four things. If you read this series in full - and hopefully you will, since over 8,000 people asked me to write this piece - you will unlock the secrets of what makes a great party, and you too will be able to organize great parties, selectively attend only those that you believe will meet the criteria, or at least have fun debating the untapped potential of a party you just left.

Axiom 1: The Optimal Party has multiple rooms, none of which are visible from one another.

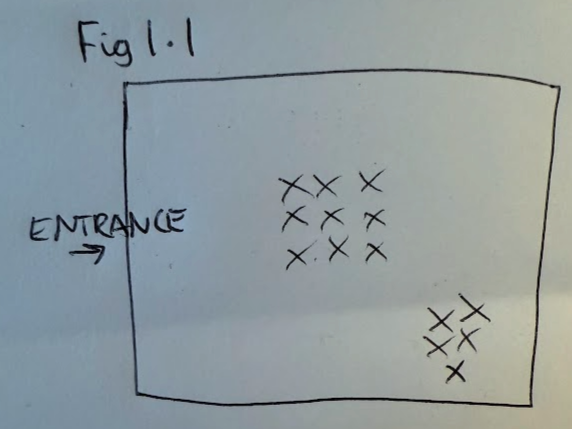

Compare the two following party layouts.

Fig 1.1: The single-room layout - a common but suboptimal party configuration

Fig 1.1 is a depressingly familiar layout - a plain, rectangular room.

Here's how it goes. You enter the party. You immediately see the whole party: a bunch of people standing in the middle of the room, or a cluster of people standing in the corner. (A person is denoted by "x" in my incredibly scientific diagrams).

So no matter what, you're stuck with one of those frustrating group chats where everyone is talking about some generic topic because they're trying to find the lowest common denominator topic across a largish group. There is little incentive for "conversational risk-taking", which always makes things more interesting.

What makes this worse, is there is little hope for respite from this, since you've seen everything there is to the party already. If there was an upstairs, or another room, you wouldn't subconcsiously be planning your exit as soon as you entered the room.

The only way this party is a good party is if the people are really great (which is, obviously, always the most important thing), or if it becomes so crowded that the room effectively splits up into multiple zones, and becomes closer to the situation in Fig 1.2.

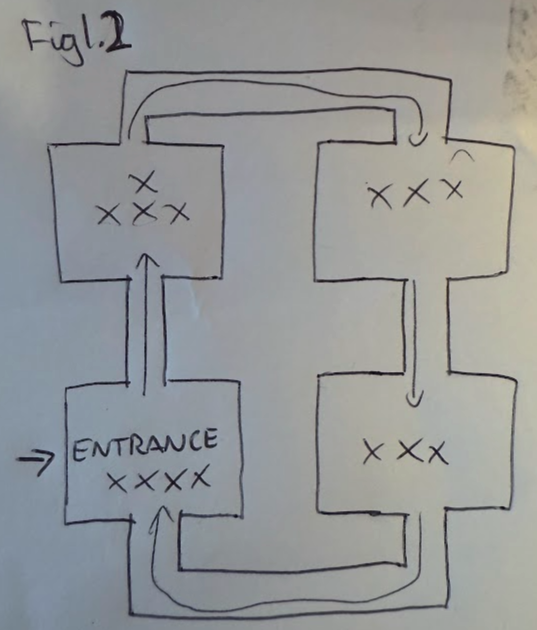

Compare the party above, then, to Fig 1.2:

Fig 1.2: The optimal layout - multiple connected rooms creating opportunities for serendipity

This is the same number of people, in the same square footage, but they are spread out in a series of connecting rooms.

Now when you enter, you see a small group you can chat to straight away, but, should this hors d'oeuvre not be to your liking, you can merely wander through to the next room, and try your luck there. The process continues - by design, the multiple rooms, none of which are visible from one another, encourage people to percolate around the party, fuelled by guests' hopes for something even better just around the corner, creating the perfect conditions for that thing that every guest, deep down, came to the party for: serendipity.

To be continued…